- Clayton Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma. I resisted reading this for a long time because it’s so much a part of the fabric of working in tech. I’m glad I did. Cost structures matter. Recommended.

- Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me. I listened to this as an audiobook, read by Coates himself. Short but powerful.

- Eric Berger, Liftoff: Elon Musk and the Desperate Early Days That Launched SpaceX. If you want to know why SpaceX can do so much in so little time, this is where to start. Great story.

- John le Carré, The Night Manager. A lot of people love le Carré; I am not one of them.

- Colin Bryar and Bill Carr, Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets from Inside Amazon. You can find a lot online about “how Amazon works.” This is the clearest distillation I’ve found.

- Brad Stone, The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon. Broad, not deep. That said, I’m looking forward to the next installment. A summary.

- Arkady Martine, A Desolation Called Peace. Solid sequel to A Memory Called Empire.

- Rick Perlstein, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. I hadn’t realized just how chaotic the late 60s early 70s were. This book filled in many gaps for me on where many of the political divides leading up to the Trump era originated. The book is overlong, and the author maintains an ironic detachment that grows tiring.

- Kim MacQuarrie, The Last Days of the Incas. Recommended. In the end it reads likes a morality tale as the original conquistadors of the Incas, almost to a man, fall to violence and betrayal.

- Ted Widmer, Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington. A strange little history book that makes a lot of connections.

- Erik Larson, The Splendid and the Vile. Engaging, but ultimately not for me.

- Barack Obama, A Promised Land. What you think this book is exactly what it is.

- David McCullough, The Wright Brothers. Really enjoyed this. I would have appreciated more about the business and patent fights of later days. You can see the Wrights slipping behind in the industry but, this is scarecely commented on.

The process is not the thing

As companies get larger and more complex, there’s a tendency to manage to proxies. This comes in many shapes and sizes, and it’s dangerous, subtle, and very Day 2.

A common example is process as proxy. Good process serves you so you can serve customers. But if you’re not watchful, the process can become the thing. This can happen very easily in large organizations. The process becomes the proxy for the result you want. You stop looking at outcomes and just make sure you’re doing the process right. Gulp. It’s not that rare to hear a junior leader defend a bad outcome with something like, “Well, we followed the process.” A more experienced leader will use it as an opportunity to investigate and improve the process. The process is not the thing. It’s always worth asking, do we own the process or does the process own us? In a Day 2 company, you might find it’s the second.

Another example: market research and customer surveys can become proxies for customers – something that’s especially dangerous when you’re inventing and designing products. “Fifty-five percent of beta testers report being satisfied with this feature. That is up from 47% in the first survey.” That’s hard to interpret and could unintentionally mislead.

Good inventors and designers deeply understand their customer. They spend tremendous energy developing that intuition. They study and understand many anecdotes rather than only the averages you’ll find on surveys. They live with the design.

I’m not against beta testing or surveys. But you, the product or service owner, must understand the customer, have a vision, and love the offering. Then, beta testing and research can help you find your blind spots. A remarkable customer experience starts with heart, intuition, curiosity, play, guts, taste. You won’t find any of it in a survey.

From Jeff Bezos’ 2016 Letter to Amazon Shareholders. The whole letter is clear, precise, and worth reading.

What I’ve been reading

- Seb Falk, The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Science. I really enjoyed this one. It draws a straight line of innovation in math and astronomy through the middle ages into the Renaissance. People in the past are always smarter than you think they were. If you ever wondered how people actually did arithmatic with Roman numerals, this is the book for you.

- Margaret Atwood, Oryx and Crake. This book has not aged well, despite and especially because of the pandemic.

- Peter Baker and Susan Glasser, The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III. One of my favorite books of 2020. Either the story of a man whose relentless operational excellence and hard work ran the nation or the story of a man with no credentials whose country club tennis partner happened to be George Bush that ran the nation. Or both.

- William N. Thorndike, The Outsiders: Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success. Necessarily surface level, but an excellent narrative introduction to the concepts of capital allocation and the value of looking at cash flow versus reported earnings.

- Mark Robinchaux, Cable Cowboy: John Malone and the Rise of the Modern Cable Business. Very inside baseball and uncritical of its subject, but I enjoyed it. Again on the theme of capital allocation and cash flow versus reported earnings.

- Matt Ridley, How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes in Freedom. An engaging polemic and history of how technological innovation happens in the real world.

- Michael Kulikowski, The Tragedy of Empire: From Constantine to the Destruction of Roman Italy. A bit inside baseball, even for me.

- Stuart Ritchie, Science Fictions: How Fraud, Bias, Negligence, and Hype Undermine the Search for Truth. Incentives rule everything.

- Ken Liu, The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories. Liu is Ted Chiang’s English translator. Beautifully written and creative.

First-team mindset

Things were simpler as an individual contributor. You understood what your teammates were up to, you chatted every day, and you knew they had your back—and you had theirs. Now you’re a people manager. On bad days, it feels like you’re stuck on an island, squinting across the water at your peers busily doing … something on their own little islands.

Sooner or later, most people managers suffer a painful day that ends with self-searching questions like:

- “Why can’t I get my team what they need?”

- “How did I not see that coming? I feel out of the loop.”

- “Why is everything so political?”

The good news is that you can take concrete actions to build the strong teammate-quality relationships you need with your peers to succeed.

Your peers are your first team

People management means playing on two teams, not one. One team consists of the people who report to you. The other team consists of your peers. This group includes people reporting the same boss as you, and more broadly, peers across the entire organization. Getting the support you need to succeed as a leader requires treating your peers as your team and not just an assortment of faces who happen to show up at staff meetings. The more senior a role you take on, the more important this becomes.

The priorities of these two teams will often, but not always, align. It’s inevitable that at some point, the demands of these dual roles will conflict. On the one hand, you now serve those who report to you—coaching, creating opportunities, sticking up for them against unreasonable demands, and shielding them from noise elsewhere in the organization. On the other hand, you now serve the entire organization you’re a part of, your peers, and the whole company. And ultimately, you are paid to deliver for the latter.

One antipattern newly promoted managers can fall into is prioritizing the interests of their direct reports over working with their new peers. The temptation is especially strong when managing people who used to be peers.

A useful way I’ve found to navigate this tension—and feel like you’re on a team again—is through what’s called a first-team mindset.

First-team mindset is treating your peers as your first team. Optimize first for your peers’ success, and second for supporting your direct reports. And yes, by treating your peers as your first team, you are treating your direct reports are your second team.

Thinking this way can feel overly hierarchical and wrong—so much of what we talk about when talking about the practice of management is serving your direct reports. However, in my experience, treating my peers as my first team is the most healthy way to operate because it motivates me to broaden my focus outward instead of narrowly focusing inward solely on my team’s immediate needs. In fact, adopting a first-team mindset enables you to serve your direct reports more effectively over the long haul.

I’ll discuss two ways to think about why a first-team mindset matters—suboptimization and relationships—and then I’ll explain six concrete actions for putting it into practice.

Suboptimization

Sometimes you will have to disappoint or cause hardship for the people you manage in order to help your peers or the company achieve big-picture objectives.

Simple but common examples of this are enforcing organization-wide standards such as supported languages and libraries, issue-tracking systems, or code review standards. While allowing an individual development team to choose whatever language they want might make it more efficient in the short term, if every team did the same, the efficiency of the entire organization would suffer as people struggled to make their code interoperate and every team had to write their own tooling. A better solution, optimized for the entire organization’s success, would be to task a platform team with writing a standard set of tooling, once, even though the standards it produces may be suboptimal for any individual front-line team it supports—including yours.

This is known as the rule of suboptimization. Making changes to improve one subsystem’s performance while ignoring the effects on the other subsystems will not lead to optimum performance of the whole. Maximizing the performance of the entire system means sub-optimizing the performance of individual parts.

Other examples include canceling a project your team is invested in or asking your team to temporarily take on an “unfair” customer support burden to support a critical customer.

This is simple enough in the abstract, but it takes courage to support and implement decisions that impose tangible negative impacts on individuals on your team.

Relationships, i.e. “politics”

Real life is messy.

Servant leadership is a wonderful mindset to adopt. But it cannot be the whole story, or at least the naive version of it can’t. Sometimes you will need to execute a decision that does not directly serve those who report to you but instead helps solve a problem for your peer’s team or helps you maintain a productive relationship with that peer.

The last one, in particular, feels a lot like the skin-crawling “politics” that everyone hates. But in the end, your team’s relationships with your peers’ teams are inseparable from your personal relationship with those peers.

Work, especially at leadership levels, is done through relationships. From the outside, this can look like politics. Many people don’t like doing it. But the alternative is not building productive give-and-take relationships with your peers. This will severely limit your ability to get things done when it’s your turn to ask your peer for help on your initiative or help take some load off your overloaded team. And you’ll always be watching your back.

Give and take is part of how humans build and maintain relationships. As an IC, you would do things personally for others on your team—take over their on-call shift so they could go to their kid’s school play, act as a sounding board for ideas, and more. You didn’t do that with a cynical view towards reciprocity, but because that’s what humans who care about and support each other do. This still applies now that you manage people. And one of the primary mechanisms of support you have available is the output of your team.

If you don’t take building relationships with your peers seriously enough to put your team’s skin in the game, then you are severely handicapping your team from getting the support they need to deliver.

Practices towards a first-team mindset

Here are some ways to put a first-team mindset into practice:

1. Know your peer’s work.

At a minimum, actively learn what your peers are working on and what they are trying to get done. Understand their incentives, their accountabilities, and their challenges. You can’t support someone if you don’t know what they need. This is also an opportunity to learn from people who may approach their work differently than you do. You can start small by dropping into your peer’s daily stand-ups, but doing this right takes work.

2. Hold regular 1:1s with your peers.

1:1s are a foundational practice for building and maintaining relationships with your direct reports. Making those appointments sacred and not to be missed ensures that you communicate regularly and sends the metacommunication that the relationship is important to you.

You can use a similar practice, the peer 1:1, to maintain your most crucial peer relationships. Here’s how:

- Identify your most important relationships. You don’t need to meet with everyone who reports to your boss, and your most important peers may report elsewhere. Focus on the peers that you work with the most or have the weakest relationship with. Start small, but aim for no more than 3-4 recurring peer 1:1s.

- Ask your peer if they would like to hold a recurring 1:1 meeting. Propose whatever cadence makes sense, but every other week or monthly are good places to start. If they are reluctant, propose a single one-off meeting to try it out.

- Tell your peer what they need to know. Make the meeting useful for them. Provide a quick, 10-minute update to them about initiatives on your team. Be open to questions.

- Build a relationship with your peer. Make a point to understand your peers as three-dimensional human beings and not just as job titles.

All of this applies doubly to people you don’t personally like. You don’t have the luxury of choosing your peers. You don’t have to be buddies to have a productive relationship.

Manager Tools has an excellent podcast on the topic.

3. Give (and graciously receive) peer feedback. Don’t “drop a dime.”

A benefit of building trusting, respectful relationships with your peers is that you can talk directly to them about real things that matter—especially when those conversations are challenging.

Ask for feedback from your peers. Graciously thank them and act on it when appropriate. This builds trust that you can take it as well as dish it out. If you’re working on a big initiative, get their input, and ask them to tell you the flaws. Not only will this result in a better product, but it will also likely result in an ally when the time comes to get others on board.

Give constructive feedback directly to your peers. It’s kinder and more respectful to talk to a peer directly instead of complaining to your boss. It’s also more effective because you can share specific details and context. No one likes being complained about behind their back, and doing so breeds distrust. Better yet, giving good-faith feedback helps drive your peer’s success, and done well, can build an even stronger relationship.

Don’t surprise your peer in public if you can avoid it. If your peer’s team is blocking your team, tell her directly and give her a chance to act on that information before calling out her team as a blocker in a staff meeting. No one likes someone dropping a dime on them. Speaking directly is both more respectful and efficient.

A metric of success is that you are talking with a peer 10x more than you are talking to your boss about that peer.

4. Trust your peers.

Respect each other’s turf. Let your peer team leads own their areas. This isn’t about staying in your lane or not engaging in productive debate, but it is about showing mutual respect. Ultimately, you don’t want them second-guessing decisions you or your team make in your area or expertise, so don’t do the same to them. Trust that they know their stuff. Let minor disagreements be.

5. Support your peer’s initiatives. Practice first follower.

Part of working together on a team of peer leaders is cooperating to drive big-picture initiatives. Sometimes cooperation means getting out of the way:

Give your support quickly to other leaders who are working to make improvements. Even if you disagree with their initial approach, someone trustworthy leading a project will almost always get to a good outcome.

The second point is vital—knowing when to exercise humility and trust when someone else’s intelligence, knowledge, experience, and drive will likely lead to good results. Commit to supporting them, even if you disagree about some of the particulars. Support drives results further than criticism.

6. Disagree and commit.

A huge advantage of working with a true team of peers is that you debate and argue about real issues, driving better, more informed decisions. But once the debate is over and a decision is made, you must support it—even if you disagree, even if it is to your team’s immediate disadvantage. Airing your disagreements with your peers serves no one, especially not your team. It only sows confusion and destroys relationships. This, admittedly, can be difficult.

If you find yourself in a situation where you find it truly ethically objectionable to support a decision, you should resign. But short of that, find a way to sincerely speak to the merits of the path forward, and lead the way.

Level up

Leading a team is not just about the people who report to you; it is about working collaboratively with your peers to accomplish initiatives that are larger than the parochial interests of your team. It’s natural to see the world through your team’s lens—after all, you spend most of your time and attention there—but your success will be limited if you cannot look beyond that. Embracing the perspective of your peers is not only how to get the support you need to succeed; it is an effective way to learn and practice thinking at the next level in your career journey. The first step is looking beyond your own island to treat your peers as your first team.

References and further reading

- The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, p. 135-138

- The Manager’s Path, “Senior Peers in Other Functions,” p. 178

- Make your peers your first team

- Building a First Team Mindset

Elsewhere on the web

— The Metronome. “Two minutes early to a meeting. As much as possible. The last act of my morning opening productivity ramp. What lessons do I demonstrate to the meeting attendees by being there two minutes early? A couple: beginning on time is respectful to attendees, and meetings are expensive affairs, so let’s invest our time wisely. There’s a more fundamental lesson I am teaching: Leaders are capable of showing up to meetings on time.”

— Receive Better Feedback by Asking and Listen, Lead, and Grow. A great two-parter about how to ask for and recieve feedback from others.

— Speak in Stories. “Too often we present our work as a series of facts. The sad truth is that most humans are bad at remembering facts. When our audience is in a related conversation days later the data we shared isn’t likely to be top of mind anymore. Our impact remains localized.”

What I’ve been reading

- Ted Chiang, Exhalation. A collection of short stories from my favorite living fiction writer. The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate and the title story, Exhalation, are my favorites in this collection.

- Gene Wolfe, Epiphany of the Long Sun. I enjoyed books 1 and 2 of the series, but I put this one down. I read for pages at a stretch with no idea what was physically happening in the story.

- Rebecca Sykes, Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art. Neanderthals are much more interesting than you think.

- David Carpenter, Henry III: The Rise to Power and Personal Rule, 1207-1258. The second book this month I put down. Well written, but I couldn’t get into it. That said, it’s interesting to read a biography of what sounds like an ineffective leader.

- Steven Levy, Facebook: The Inside Story. A few technical howlers, but an engaging telling of the founding and growth of Facebook. I would have liked more detail on either the technology or the management practices.

Steve Jobs always gets it right

Fucking Steve always gets it right. … Steve really always gets it right. I mean it, precisely, like an engineer. I am not joking, and I am not exaggerating. … I didn’t say Steve is always right. I said he always gets it right. Like anyone, he is wrong sometimes, but he insists, and not gently either, that people tell him when he’s wrong, so he always gets it right in the end.

Andy Grove, as quoted in Radical Candor, by Kim Scott.

This is an interesting distinction. Steve Jobs is sometimes hagiographized as the always-right visionary genius, but the truth is more interesting. One story comes to mind: Apple’s decision in 2003 to bring iTunes to Windows.

Jobs was adamantly opposed, at one point shouting that letting iTunes and the iPod run on Windows would only happen “Over my dead body! Never! We need to sell Macs! This is going to be why people buy Macs!”

His team had to battle him loudly, many times to convince him. It wasn’t pretty. Jobs deflected responsibility for the decision. But he finally was convinced that the upside of increasing iPod sales would outweigh the downside of potentially fewer Mac purchases in the short term. So in the end Apple got it right, setting the stage for Apple’s resurgence, the iPhone, and everything that followed. This was the result of the Apple leadership team doing its job and telling Steve Jobs that he was wrong.

If even the most celebrated visionary can be wrong, you can be too, and so can your boss. Have the courage and humility to seek the truth, and the conviction to act.

Definite vs. indefinite thinking: Notes from Zero to One by Peter Thiel

Peter Thiel is a controversial figure for a good reason. But he’s also brilliant, accomplished, and takes (for better and worse) unpopular public stances. His track record of success makes him worth listening to.

Zero To One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future is a collection of his thoughts about Silicon Valley startups. It is very much attuned to that particular environment, but I recommend it if you work in software anywhere. It’s easily digestible even as an audiobook.

Thiel covers a fair amount of ground, but I’m going ignore most of it in favor of discussing the one idea that’s stuck with me: his framing of definite thinking versus indefinite thinking.

He argues that you can choose to think of the future in either definite or indefinite terms, and that choice has a real effect on how you approach and live your life:

You can expect the future to take a definite form or you can treat it as hazily uncertain. If you treat the future as something definite, it makes sense to understand it in advance and to work to shape it. But if you expect an indefinite future ruled by randomness, you’ll give up on trying to master it. … Process trumps substance: when people lack concrete plans to carry out, they use formal rules to assemble a portfolio of various options. … A definite view, by contrast, favors firm convictions.

Indefinite attitudes, he argues, explain much of what’s dysfunctional in today’s world. It’s a hyperbolic statement but worth thinking about. I certainly have a lot of (well-founded?) cynicism about our society’s ability to define, plan, and take on big challenges, which has only increased with COVID-19. This is most obvious at the federal level—it is tragic how little of federal stimulus money this year went to projects that actively and concretely tried to combat the actual threat that we faced. (Project Warp Speed, despite the controversy surrounding it, is a fortunate counterexample, along with the incredible acceleration of scientific research across the world.)

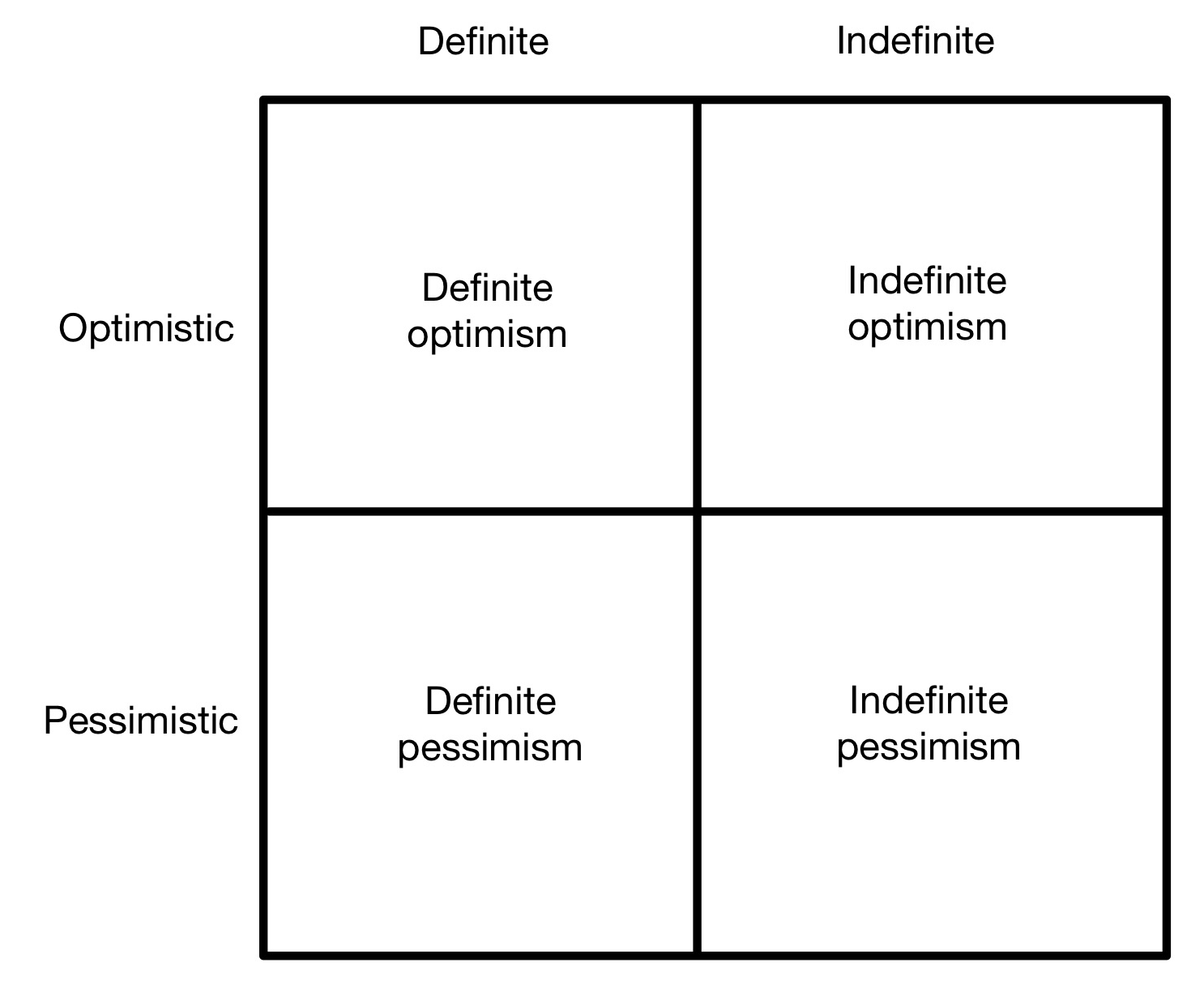

Thiel defines four quadrants combining the two axes of definite/indefinite thinking and optimism/pessimism:

Let’s cover these in turn:

- Indefinite Pessimism. “An indefinite pessimist looks out onto a bleak future, but he has no idea what to do about it.”

- Definite Pessimism. “A definite pessimist believes the future can be known, but since it will be bleak, he must prepare for it.”

- Indefinite Optimism. “To an indefinite optimist, the future will be better, but he doesn’t know how exactly, so he won’t make any specific plans. He expects to profit from the future but sees no reason to design it concretely.”

- Definite Optimism. The future will be better than the present if you make plans and work to make it better. “From the 17th century through the 1950s and ’60s, definite optimists led the Western world. Scientists, engineers, doctors, and businessmen made the world richer, healthier, and more long-lived than previously imaginable.” Thiel gives some of the expected examples of the Golden Gate Bridge (1933-1937), The Manhattan Project (1941-1945), and the Interstate Highway System (1956-1965).

Thiel contends that the U.S. since 1982 (Reagan) has been defined by indefinite optimism, exemplified by the rise of finance as a driver of the economy. We believe in progress; we just don’t believe in planning for it:

Instead of working for years to build a new product, indefinite optimists rearrange already-invented ones. Bankers make money by rearranging the capital structures of already existing companies. Lawyers resolve disputes over old things or help other people structure their affairs. And private equity investors and management consultants don’t start new businesses; they squeeze extra efficiency from old ones with incessant procedural optimizations.

Definite vs. indefinite thinking is about agency. If you see the future only indefinitely, there is no reason to plan. It’s something that happens to you, not something you can create. Therefore, embracing definite optimism is the way to create a better future.

The other three views of the future can work. Definite optimism works when you build the future you envision. Definite pessimism works by building what can be copied without expecting anything new. Indefinite pessimism works because it’s self-fulfilling: if you’re a slacker with low expectations, they’ll probably be met. But indefinite optimism seems inherently unsustainable: how can the future get better if no one plans for it?

This brings to mind the famous Steve Jobs quote, “We’re here to put a dent in the universe. Otherwise why else even be here?” John Siracusa, in his remembrance of Steve Jobs, said this:

I was 9 years old at the time. … My grandfather also had a subscription to Macworld magazine, including multiple copies of issue #1, two of which I took home with me. I cut the Macintosh team picture out of one and left the other intact. (I still have both.)

I pored over that magazine for years, long after the technical and product information it contained was useless. It was the Macintosh team that fascinated me. That’s why I’d chosen to cut out this particular picture, not a photo of the hardware or software. After seeing the Macintosh and then reading this issue of Macworld, I had an important realization in my young life: people made this.

The Macintosh was the first thing in my life that I recognized as being wholly new. Everything I’d seen thus far in my nine years had seemed like it already existed prior to my birth—perhaps like it had always existed. But here was something different, something amazing, and this magazine explained how it had been created by this small group of people.

The implications bloomed in my mind. We aren’t stuck with the things we have now. We can make new things, better things. And it doesn’t take many people to do it. The team that had created this mind-bending new machine were all up on my wall, their individual faces clearly recognizable.

That is: those with a definite vision for the future are the ones who can actually build the future. Thiel argues that in contrast, the common belief in modern software practice in incrementalism—that the best way forward is small, iterative, adjacent steps—diminishes potential:

Even in engineering-driven Silicon Valley, the buzzwords of the moment call for building a “lean startup” that can “adapt” and “evolve” to an ever-changing environment. Would-be entrepreneurs are told that nothing can be known in advance: we’re supposed to listen to what customers say they want, make nothing more than a “minimum viable product,” and iterate our way to success.

But leanness is a methodology, not a goal. Making small changes to things that already exist might lead you to a local maximum, but it won’t help you find the global maximum. You could build the best version of an app that lets people order toilet paper from their iPhone. But iteration without a bold plan won’t take you from 0 to 1. A company is the strangest place of all for an indefinite optimist: why should you expect your own business to succeed without a plan to make it happen?

In other words, for a company to be great, it needs to create for itself a concrete vision for the future that is different and better in some fundamental way from the present. This sounds grandiose, but it is an excellent way to encapsulate the goal of building and delivering a unique and superior product to your customers. It is creating a future that other people have not yet imagined.

Thiel’s discussion made me realize that I can tend toward indefinite thinking. By nature, I am suspicious of the Big Plan and gravitate towards refining already existing processes and products. This, perhaps uncoincidentally, is the same trap that I see many Agile practitioners fall into. Sprints lead people towards a two-week planning horizon. Which is a feature! But I have found that if I’m not careful, this approach’s clear tactical advantages and comfort can lead to myopia and discourage me from committing to a concrete and big-picture strategy. Long-term planning is not just for waterfall development.

It’s easy for cynicism about the world and our ability to change it to prevent us from making big concrete plans for the future, or worse, from imagining a future that is better in some big, tangible way from the present. It can cause us to turn our focus inward toward relative status games or internal company politics instead of outwards toward the wider world and what we’re trying to build. It’s this diminishment of the imagination that I think is a real tragedy and something I am now trying to guard against in my own thinking.

Thiel issues the challenge to think bigger, be a definite optimist, and be determined to shape the future to your vision, even if in a small way, make a plan, and do the work. Even if the universe is too big for most of us to make a dent in it, this approach has to be better than capitulating to indefinite cynicism about the future.

What I’ve been reading

I’ve never been into audiobooks, but I’ve taken up listening to them while exercising. I like it and feel better about it than listening to yet another podcast about Apple products.

- Michael Lewis, The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds. An accessible narrative introduction to Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s work around heuristics and decision-making. And they led fascinating lives! Their representativeness heuristic is another way of looking at why narrative stories are so powerful, for better and worse. I hope to follow up with Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow.

- David Wolpe, David: The Divided Heart. Not a story I knew much about.

- Peter Thiel and Blake Masters, Zero To One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future. A lot to think about in this one, particularly around definite vs. indefinite thinking.

- Kim Stanley Robinson, Red Moon. No, it’s not related to the Red Mars series. Vintange Robinson. He published this in 2018, so it was sad how its depiction of Hong Kong in 2047 is already out of date, and not a good way.

- Ibram X. Kendi, How To be an Antiracist. An important book with an important message, but for me, could have been more powerful if it focused more on making its central arguments and less on defining new terms.

- Kevin Davies, Editing Humanity: The CRISPR Revolution and the New Era of Genome Editing. Once I got past the throat-clearing, this is an interesting story about how science actually works.