One idea I’ve found surprisingly useful is summed up in a single sentence: While it is important to make the right decision, it is more important to do the work to make the decision right.

This idea puts the focus on implementation as the fulcrum of a successful decision. It shows why quickly making and acting upon a good-enough decision can be better than spending a long time analyzing and searching for the perfect decision. And it shows why Agile’s iterative approach to minimizing decision size can be so effective.

I’ll discuss this by way of engineering management, but the principles apply widely. I won’t discuss the process of reaching decisions, even though I believe that almost everyone can benefit from trying a more systematic and rigorous approach.

1. There are no “right” and “wrong” answers

When making a decision in a complex environment (i.e., the real world), there usually isn’t an objectively “correct” answer. This can be hard to accept: in school, we’re assigned math problems, and those problems have clear and correct answers, printed in the back of the book or marked up in red by a teacher.

Decisions in real life (mostly) aren’t like this, especially as you advance in your career and face decisions of greater importance and ambiguity. Which technology stack do you choose? Do you prioritize Project Orange Traffic Cone or Project Halibut? Do you stay at your current gig, or jump ship to a new one? Complex decisions like these rarely have unambiguous, objective, correct answers.

There are a few reasons for this. First, the consequences of a decision are sometimes known only much later. Even then, it may be impossible to evaluate it against the possible alternatives that were available at the time. And it can be hard even to know how to evaluate a decision, even in retrospect. Sometimes a decision was wrong from day one. But other times, a decision becomes wrong because of a change in circumstances.

Second, sometimes there isn’t a 100% right answer, only answers with mutually exclusive tradeoffs. (“Good, fast, cheap. Choose two.”)

Third, in almost any complex decision, the different people involved will bring different facts and judgments about relevance. Marketing can have very different ideas of what information matters in a product decision than engineering.

And fourth, there can be disagreement about what the desired high-level objective of the decision even is. For example, suppose you decide to work on Project Orange Traffic Cone over Project Halibut. That decision is intended to achieve a high-level goal: to deliver the product that will be the most profitable. Or perhaps the product that is most useful to customers. Or that best fits into the company’s higher-level strategy. Or something else. Different people judge success (or failure) differently, in sometimes mutually exclusive ways. You can work to achieve alignment on this, but people will often have criteria that are important to them, tied up in their own goals or the perceived impact on their relative status.

2. The output of a decision is its consequences

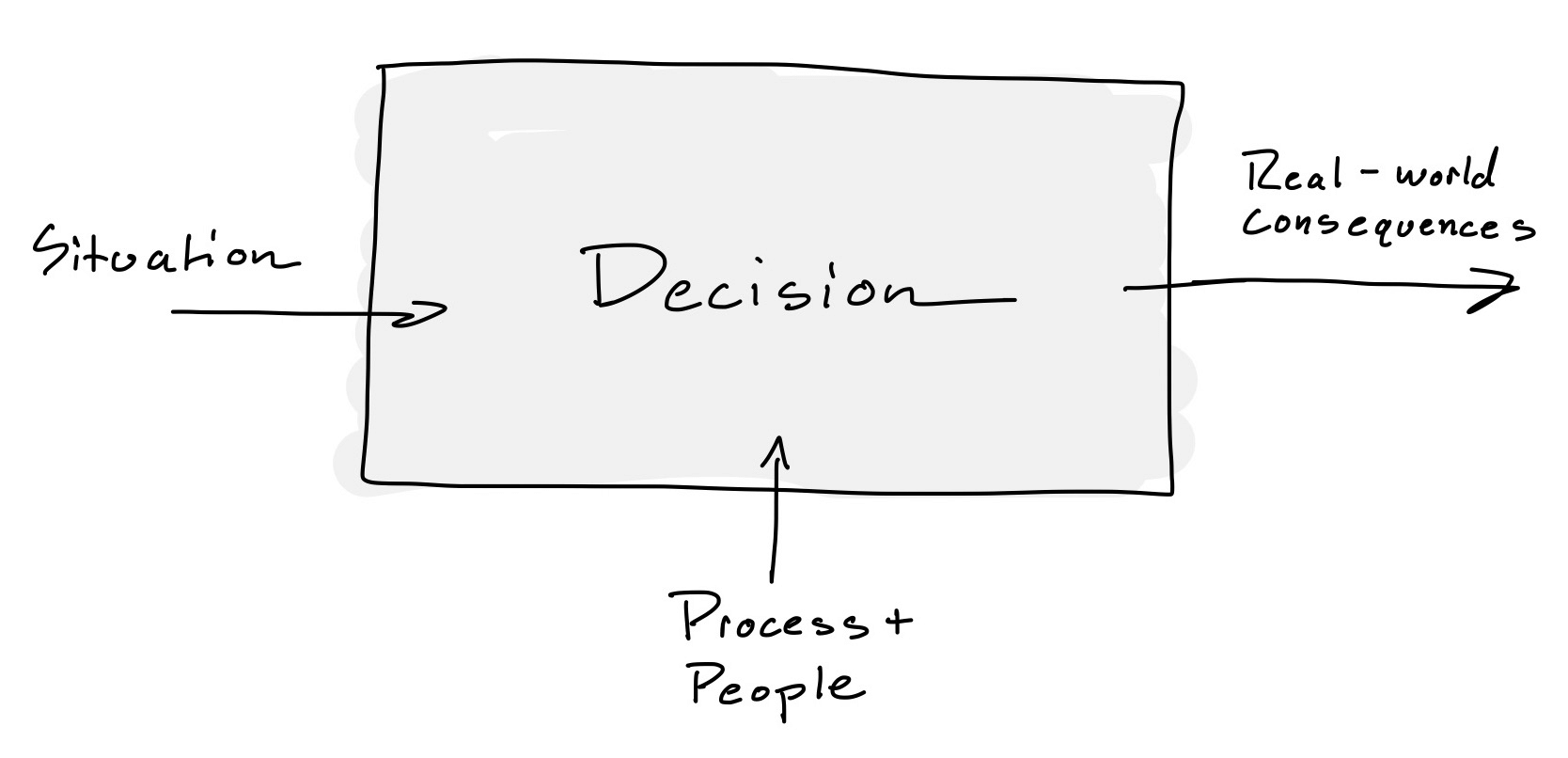

The purpose of a decision is to create consequences in the real world, so the best way to evaluate a decision’s effectiveness is through those consequences.

It’s useful to think of a decision as if it were a “black box”: input (a situation in the world and the people and processes involved in making a decision) flowing in, and the output (real-world consequences) flowing out:

This is what a decision looks like from the outside to someone uninvolved. How a decision is made—what happens in the box—is irrelevant to its observable consequences. For example, if you decide to hire someone for your team with great qualifications after a rigorous interview process, and then three months later, this person bails on you, that’s not a successful consequence. It is not a successful decision.

Yes, the decision-making process matters! But those processes have limitations, and what ultimately what matters are actual results. Customers don’t care about your decision-making process. Decisions are a means to an end, and that end is real-world consequences.

3. At the moment you make a decision, it is impossible to know if it is good or bad

A decision is measured by its output (real-world consequences), not by a theoretical accounting of whether it is good or bad. So you can’t evaluate its quality until time has passed and those consequences are clear. Of course, in some situations, you may never know if the decision was the best choice out of the available options since you can’t run the counterfactual.

4. A decision itself changes nothing

A decision doesn’t have any observable output—real-world consequences—unless you act on it. Merely changing your mental state does not create consequences in the real world. The execution of the decision is part of the decision.

Chris Voss touches on this in Never Split the Difference while talking about negotiated agreements:

“Yes” is nothing without “How.” While an agreement is nice, a contract is better, and a signed check is best. You don’t get your profits with the agreement. They come upon implementation. Success isn’t the hostage-taker saying, “Yes, we have a deal”; success comes afterward, when the freed hostage says to your face, “Thank you.”

Let’s say you decide to buy a new car. Until you sit down, do research, visit dealerships, and finally write a check, what you have is an intention but not a decision. Considering the concrete implementation is a good way to clarify your decision-making: you can’t decide to buy a BMW if you don’t have the money and don’t qualify for a loan.

In the Effective Executive, Peter Drucker writes:

Converting the decision into action is the fourth major element in the decision process. While thinking through the boundary conditions is the most difficult step in decision-making, converting the decision into effective action is usually the most time-consuming one. Yet a decision will not become effective unless the action commitments have been built into the decision from the start.

In fact, no decision has been made unless carrying it out in specific steps has become someone’s work assignment and responsibility. Until then, there are only good intentions.

Converting a decision into action requires answering several distinct questions: Who has to know of this decision? What action has to be taken? Who is to take it? And what does the action have to be so that the people who have to do it can do it? The first and the last of these are too often overlooked—with dire results.

How many meetings have you been in with energetic discussion, everyone’s excited, decisions were made, and then … nothing happens? No one took responsibility for action items. No one followed up. In the end, all you had was good intentions.

5. You will spend more time living with the consequences of a decision than deciding the first place

This is the crux. You and the team decided to tackle Project Orange Traffic Cone. Even if you followed a rigorous process, thoroughly discussed the question with the team and with stakeholders to gain consensus—all things that take time—the development team will spend far longer implementing that decision (building Project Orange Traffic Cone) than the time it took to reach the original decision point. So how you act is as crucial to the outcome as the “rightness” of the decision itself.

So let’s talk about execution.

Execution is where you make the decision right

For example, let’s say you made the “wrong” decision and worked on the “wrong” project. Maybe Project Halibut theoretically had more financial upside than Project Orange Traffic Cone. So you blew it? Maybe. But there’s still a high chance that delivering Project Orange Traffic Cone quickly, nailing the implementation, and listening to user feedback and iterating is more profitable than a late and haphazard implementation of Project Halibut. Skill and rigor and energy of execution can sometimes—although not always—make up for a suboptimal initial decision.

The output of a decision is its real-world consequences, and execution is the forge where those consequences are constructed. Execution is where a decision becomes real, and where operational excellence, skill at craft, rigorous project management practices, communicating an elevating purpose, and even the psychological safety and intrinsic motivation of a team become determining factors. It’s time to do the work.

Feedback and iteration are part of execution

Once a decision has been made and committed to, it is effectively a sunk cost. It is done. But… And here is the critical point—that does not mean marching blindly forward. Listening to feedback about the decision, observing the real world, and adapting are all critical to implementing the decision.

Peter Drucker, again in The Effective Executive:

Finally, a feedback has to be built into the decision to provide a continuous testing, against actual events, of the expectations that underlie the decision. … Even the best decision has a high probability of being wrong. Even the most effective one eventually becomes obsolete.

…

To go and look for oneself is also the best, if not the only, way to test whether the assumptions on which a decision had been made are still valid or whether they are becoming obsolete and need to be thought through again. And one always has to expect the assumptions to become obsolete sooner or later. Reality never stands still very long. Failure to go out and look is the typical reason for persisting in a course of action long after it has ceased to be appropriate or even rational.

Another way to think of this is that action generates new information, which then allows you to make better decisions. The information you create by acting is often very high quality and more valuable than insight generated through passive analysis. A trite example is that you can learn faster about product/market fit by launching an MVP and getting real customers to use it than you can by doing a lengthy abstract market analysis.

Once you are acting, you are generating new information. Even if your initial decision is wrong, you can almost by definition make a better second (or third, or fourth) decision because you now have more high-quality information and real-world feedback to work with.

Work to minimize decision size: Decision making and Agile

Agile as a methodology and philosophy is focused on compensating for the impossibility of humans making correct, up-front decisions in the face of complexity. Instead, Agile encourages making a series of small decisions, acting on those decisions, and continually adapting and iterating based on real-world feedback from real users. It recognizes that shipping software creates new information about what software you should be building. If you can minimize your time to ship, you can get that information faster.

In other words, you should minimize decision size: avoid big decisions in favor of a sequence of smaller decisions. This is captured in the first three principles of the Agile Manifesto:

- Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

- Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.

- Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale.

In scrum, a team works in two-week sprints. At the beginning of a sprint, the team decides on a high-level outcome and selects the work to achieve it. After a sprint, the team holds a retrospective to reflect on how they worked and then plans the next sprint—deciding the subsequent outcome to achieve. Structured reflection and iteration are built directly into the execution.

Another feature of the two-week sprint is that it is a forcing function on decisions and execution. It’s hard to ship software when you can always add another feature, fix another bug, polish things a bit more. When you have a sprint deadline, you must make decisions about tradeoffs quickly, which allows you to generate new information through acting.

Conclusion

Deciding is inseparable from doing. And ultimately, it is the doing that makes the difference.

The purpose of making a decision is to change something in the world and make something happen that would have not otherwise happened if you did not act. It is one thing to make up your mind that something should change—problems are not hard to find—and another to do the prolonged hard work of building something in the real world. It’s one thing to have an intention and quite another to get out of your chair and act.

The world doesn’t need more good intentions; it needs more useful actions. It needs people to build, execute, and to create the future. It needs people to do the unglamorous plain old hard work of taking the mind-stuff of a decision and making it real. It needs people to act in small ways with integrity every day. It needs people to make decisions right.