“It’ll be a disaster,” Marie says. Her eyes narrow, and she raps the table. “We don’t have the people and we’ve never used that stack in production.”

Devon, who’s been silent for the entire team meeting, nods, just barely.

Angela’s heart rate spikes. Yesterday the company’s biggest customer asked—demanded really—a new feature nowhere on the roadmap with hairy technical implications. Angela, the team’s tech lead, immediately sprung into action, whiteboarded with other tech leads and senior engineers on her team and across the company, and even endured an interminable one-hour phone call with that one sales guy she can’t stand. Nobody likes the situation, but Angela is proud of the plan she worked hard to put together. It’s a good plan.

And now this.

The hairs on the back of Angela’s neck prick up. Marie’s only been on the team for what, a month? She takes a breath.

“You’re wrong.”

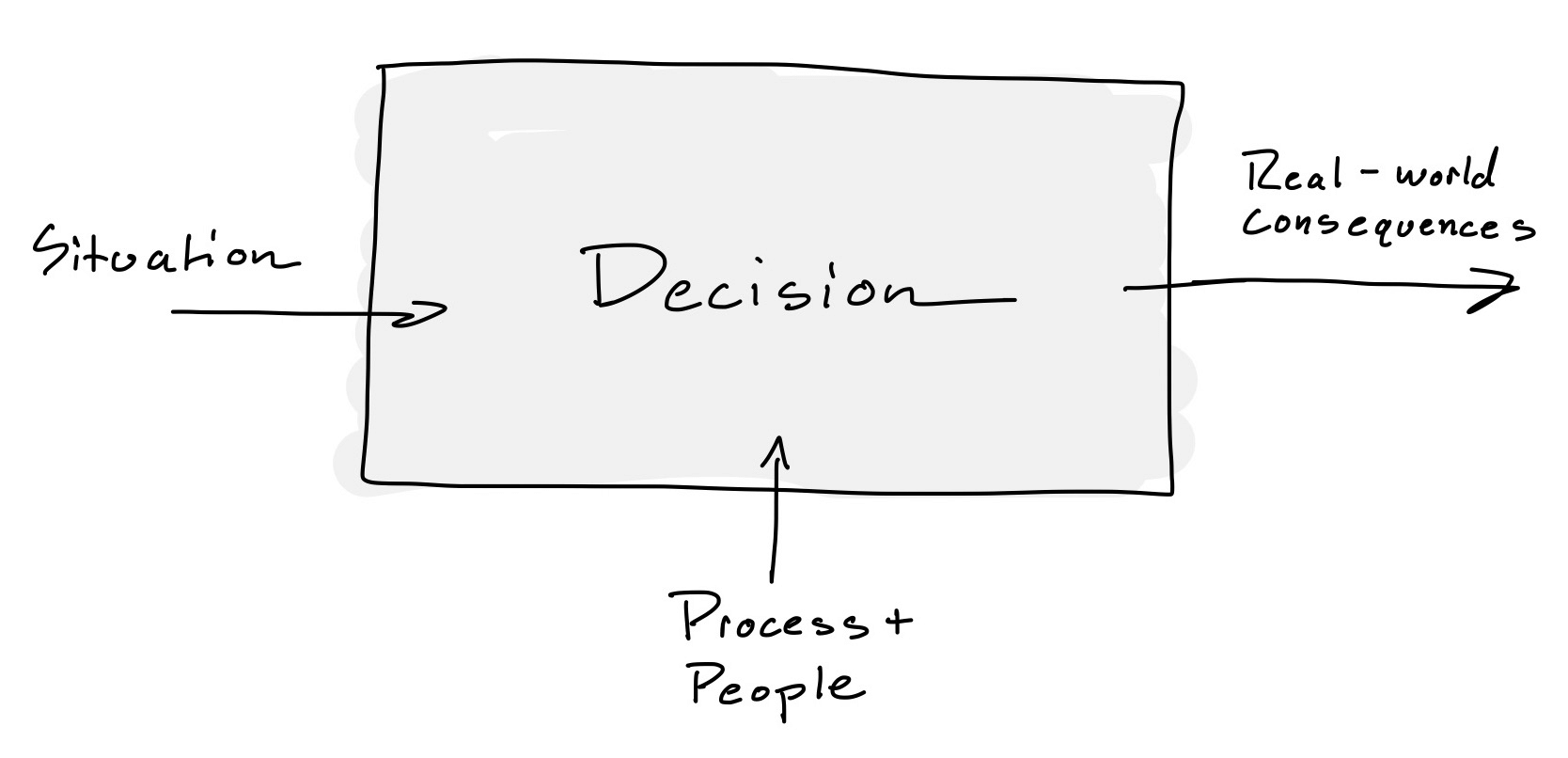

Disagreement is inevitable on any team: whenever two or more humans come together, they bring differing knowledge, context, and motivations. This is healthy, but that doesn’t prevent the words “you’re wrong” from physically wrenching you into fight-or-flight.

Reacting to that feeling, digging in, and aggressively arguing your case is almost always counterproductive. Instead, disagreement is an opportunity to learn something, and maybe counterintuitively, build a stronger relationship by grappling honestly with another person’s perspective. All of this starts with being willing to recreate and acknowledge the other person and accept what they are saying without resistance, even if—especially if—you just know they are wrong.

Acceptance is not agreement: You can fully accept what someone is saying and still wholly disagree with it. You can acknowledge that understanding without looking weak, giving in, or committing to any action you don’t want to. Showing acceptance in the face of disagreement is an act of kindness, it builds knowledge, and it increases your influence and ability to drive agreement.

If you’re doing your job as an engineering leader, you should face disagreement all the time. You should encourage it! Being able to listen and explain your position without disempowering is a critical behavior of a leader.

Acceptance is a kindness

“It all starts with the universally applicable premise that people want to be understood and accepted. Listening is the cheapest, yet most effective concession we can make to get there.” - Chris Voss, Never Split the Difference

Actively listening to someone and accepting what they are saying is kind. Just think of how agonizing it can feel to be misunderstood, alone, or that no one listens when you talk. Lifting this burden from someone is a gift.

The key is to truly listen, don’t just hear. Don’t just shut up long enough to let the other person talk, nodding along until you get your turn. Don’t just murmur empty sounds of sympathy. That doesn’t accomplish anything. You should tune into and try to grasp their underlying ideas, feelings, and motivations. If done well, you can start to see what’s underneath the surface-level facts.

You may have to ask direct clarifying questions. That can feel uncomfortable and weird:

- “It sounds like you are angry about this.”

- “It sounds like you think I didn’t consider the team’s thoughts about this.”

- “What I’m hearing is that you’re fine about this decision, but from your body language, it looks like you have doubts.”

This is hard work! And it can feel downright impossible if your adrenaline is pumping because you disagree about something that matters. In Crucial Conversations, the authors refer to this as “exploring others’ paths.” They recommend focusing intently on your sense of curiosity about the mystery of the other person:

To keep ourselves from feeling nervous while exploring others’ paths—no matter how different or wrong they seem—remember we’re trying to understand their point of view, not necessarily agree with it or support it. Understanding doesn’t equate with agreement. Sensitivity does equate to acquiescence. … There will be plenty of time later for us to share our path as well. For now, we’re merely trying to get at what others think in order to understand why they’re feeling the way they’re feeling and doing what they’re doing.

Once you think you understand what a person is saying, summarize it back to them in your own words to confirm. If you find this a struggle, have a go-to phrase you can use. For example: “Let me see if I follow what you’re saying. What this looks like from your point of view is…”

Repeat until you get it right. And thank them.

Note that nothing here involves apologizing, agreeing with them, or saying that you are wrong.

Acceptance can build knowledge

Beliefs are hypotheses to be tested, not treasures to be guarded. - Philip Tetlock

If you succeed at grappling with someone’s perspective, a magical thing may happen: you may learn where you are mistaken.

It may be flaws in your reasoning. Or facts that were hidden from you. Or maybe that you’re just plain wrong. If you can manage to listen in this way, you’ll invariably learn something. People bring different facts to the table because they know different things, have talked to different people, and spend their time thinking about things that you don’t. It’s foolish to ignore that! It’s not your job to have all the answers.

Acceptance can build consensus

One of the best ways to persuade others is with your ears—by listening to them. - Dean Rusk

The quickest way to ensure someone never changes their mind is to try to ram something down their throat. Just think about how you would feel! However, by showing that you are genuinely open to what they are saying, you signal that you yourself are open to change, and therefore, make the other person feel a little bit safer about being open to change themselves. People will not listen unless they feel listened to. Consensus is not achieved by steamrolling or by downplaying someone else’s opinions.

From Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In:

Unless you acknowledge what they are saying and demonstrate that you understand them, they may believe you have not heard them. When you then try to explain a different point of view, they will suppose that you still have not grasped what they mean. They will say to themselves, “I told him my view, but now he’s saying something different, so he must not have understood it.” Then instead of listening to your point, they will be considering how to make their argument in a new way so that this time maybe you will fathom it.

Reaching consensus is not about rationally weighing objective facts. It is a narrative. Each person needs to be able to tell themselves a story in which they are the protagonist who is respected, heard, and acts with autonomy. When someone makes an argument, they are (1) presenting their facts for judgment, but more importantly, they are (2) putting up their story, and themselves, for validation. Acceptance—even without agreement—is the first step towards consensus.

As a leader and a human, be committed to getting to the right outcome, but not invested in personally being right. You don’t look like less of a leader by listening intently and being open to change. People respect the ability to accept criticism with grace more than you might think. It’s hard! People get that.

Don’t let your fear of giving in dissuade you from engaging with and understanding someone else’s perspective. You’ll usually learn something. You can’t make everyone happy all of the time, but if you work at it, you can make everyone feel respected and heard.

Listen

Angela listens. She asks questions. She repeats and summarizes. She bites her lip.

“I just don’t like being jerked around,” Marie says. She looks straight at Angela, then exhales. “I think if we get some support from an SRE up front, this can work.”

Angela nods. “I like that. I’ll see what we can do.”